When a website underperforms, the response is almost always the same: redesign it.

The layout must be outdated.

The messaging must be wrong.

The technology must be holding us back.

So the company commissions a new site, migrates platforms, refreshes the brand, and launches with optimism. For a brief moment, everything feels better. Then, slowly, the familiar problems return. Traffic doesn’t convert. Leads aren’t right. Internal teams disagree about what the data means. Leadership starts asking why, after all this effort, the website still isn’t delivering.

At that point, the conclusion is usually implicit but powerful: the website is the problem.

In most cases, that conclusion is wrong.

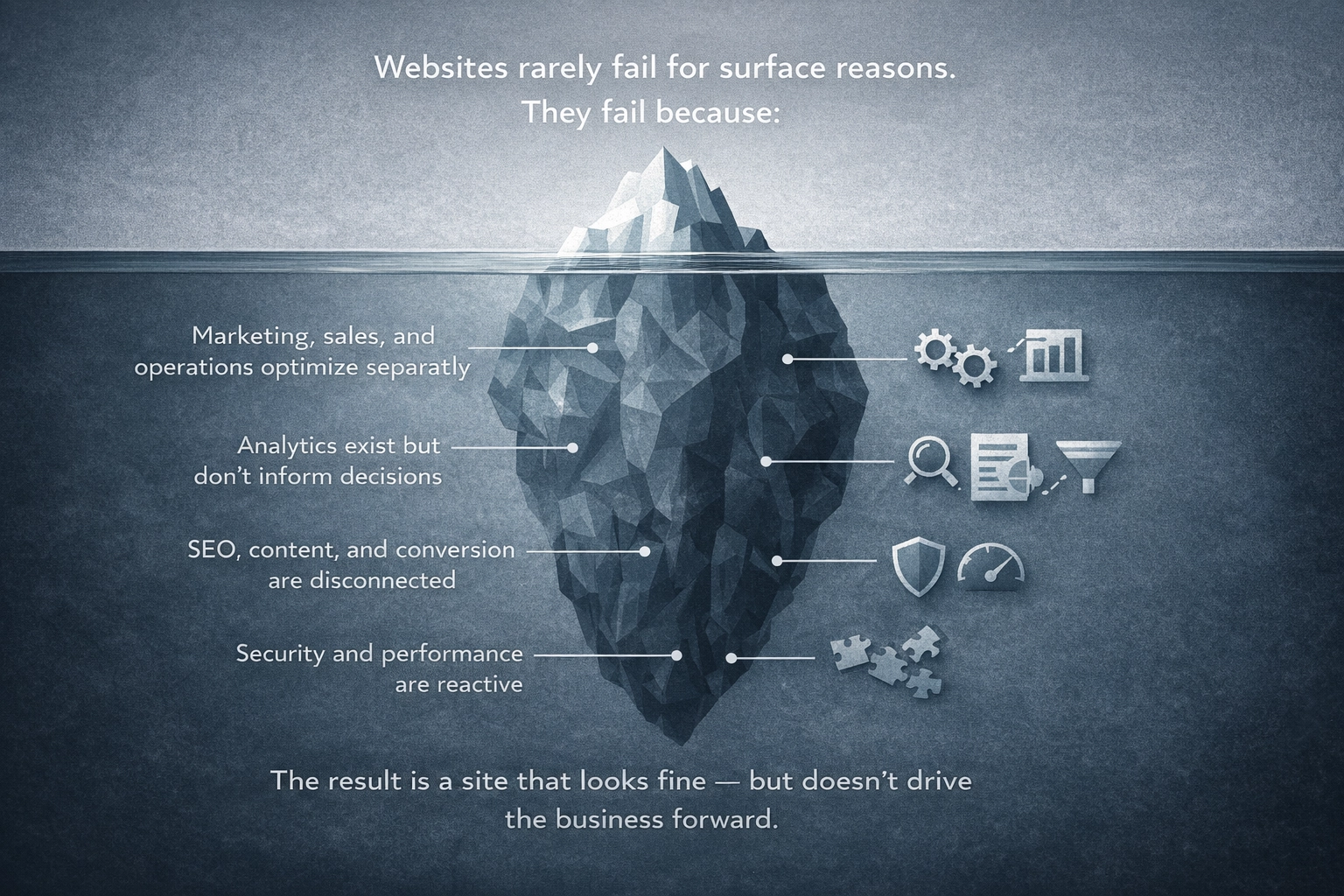

Websites rarely fail because of surface issues. They fail because they are treated as isolated artifacts instead of as components within a larger business system. When that system is misaligned, the website simply reflects that reality—no matter how polished it looks.

The Mistake That Keeps Repeating

The modern website is often framed as a project. Something to be planned, built, launched, and handed off. This framing made sense when websites were essentially digital brochures. It no longer does.

Today, a website sits at the intersection of marketing strategy, sales processes, operational constraints, analytics, security, and customer behavior. It absorbs decisions made across the organization and exposes their inconsistencies to the outside world.

When those surrounding systems don’t work together, the website becomes the visible surface where deeper misalignments show up. Redesigning it is like repainting a cracked wall without addressing the foundation beneath it.

This is why so many redesigns feel productive but change very little.

What Failure Actually Looks Like

When companies say their website “isn’t working,” what they are often experiencing is a sense of drift. Everyone is busy, initiatives are underway, and yet outcomes don’t improve in proportion to the effort invested.

Marketing pushes traffic, but sales complains about lead quality. Analytics reports exist, but decisions still default to intuition or hierarchy. Content is produced, yet it doesn’t seem to guide visitors toward meaningful action. Performance and security become urgent only when something breaks, at which point fixes are reactive and costly.

Individually, none of these issues look catastrophic. Together, they form a system that cannot reliably produce the outcome leadership expects. The website becomes the messenger that delivers bad news, even though it didn’t cause the problem.

Why the Website Gets Blamed

The website is visible. The system around it is not.

It is much easier to critique a homepage than to examine how incentives shape behavior across teams. It is simpler to change a CMS than to clarify who actually owns digital outcomes. It feels more concrete to debate design than to confront the fact that no shared model exists for how the business turns attention into revenue.

So the website becomes the proxy for deeper uncertainty. Fixing it feels actionable. Questioning the system feels abstract and uncomfortable.

But abstraction is precisely where the real constraints live.

The Shift That Changes Outcomes

Organizations that escape this cycle don’t start with a better design brief. They start with a different question.

Instead of asking how the website should look, they ask how it is supposed to function within the business. What decisions does it need to support? What behaviors should it encourage or discourage? What assumptions is it encoding about customers, sales cycles, and capacity?

Seen this way, the website becomes less of a deliverable and more of a diagnostic surface. It reveals where handoffs break, where feedback loops are weak, and where local optimization undermines global outcomes.

At that point, improvement stops being cosmetic. It becomes structural.

When the System Changes, the Website Follows

When marketing, sales, operations, and analytics are aligned around a shared understanding of the system they are part of, the website’s performance often improves without dramatic intervention. Messaging becomes clearer because it reflects real priorities. Data becomes useful because it informs actual decisions. Changes compound instead of resetting with each new initiative.

This doesn’t mean the website never needs to change. It means those changes are now informed by context rather than guesswork. They fit within the system’s capacity instead of overwhelming it.

The result is not a “perfect” website. It is a resilient one—capable of evolving without constant reinvention.

The Work That Actually Matters

Improving a website in any meaningful sense rarely starts with wireframes or technology choices. It starts with making the system visible: the constraints that shape behavior, the incentives that guide decisions, and the coordination limits that determine what is realistically possible.

This kind of work is quieter than a redesign. It doesn’t produce immediate visual artifacts. But it prevents the expensive, repeated failure cycles that so many organizations accept as normal.

Websites don’t fail because they are poorly built.

They fail because they are asked to succeed inside systems that cannot support the outcome.

Change the system, and the website usually takes care of itself.

Your Website Isn’t Failing. The System Around It Is.

When a website underperforms, the response is almost always the same: redesign it.

The layout must be outdated.

The messaging must be wrong.

The technology must be holding us back.

So the company commissions a new site, migrates platforms, refreshes the brand, and launches with optimism. For a brief moment, everything feels better. Then, slowly, the familiar problems return. Traffic doesn’t convert. Leads aren’t right. Internal teams disagree about what the data means. Leadership starts asking why, after all this effort, the website still isn’t delivering.

At that point, the conclusion is usually implicit but powerful: the website is the problem.

In most cases, that conclusion is wrong.

Websites rarely fail because of surface issues. They fail because they are treated as isolated artifacts instead of as components within a larger business system. When that system is misaligned, the website simply reflects that reality—no matter how polished it looks.

The Mistake That Keeps Repeating

The modern website is often framed as a project. Something to be planned, built, launched, and handed off. This framing made sense when websites were essentially digital brochures. It no longer does.

Today, a website sits at the intersection of marketing strategy, sales processes, operational constraints, analytics, security, and customer behavior. It absorbs decisions made across the organization and exposes their inconsistencies to the outside world.

When those surrounding systems don’t work together, the website becomes the visible surface where deeper misalignments show up. Redesigning it is like repainting a cracked wall without addressing the foundation beneath it.

This is why so many redesigns feel productive but change very little.

What Failure Actually Looks Like

When companies say their website “isn’t working,” what they are often experiencing is a sense of drift. Everyone is busy, initiatives are underway, and yet outcomes don’t improve in proportion to the effort invested.

Marketing pushes traffic, but sales complains about lead quality. Analytics reports exist, but decisions still default to intuition or hierarchy. Content is produced, yet it doesn’t seem to guide visitors toward meaningful action. Performance and security become urgent only when something breaks, at which point fixes are reactive and costly.

Individually, none of these issues look catastrophic. Together, they form a system that cannot reliably produce the outcome leadership expects. The website becomes the messenger that delivers bad news, even though it didn’t cause the problem.

Why the Website Gets Blamed

The website is visible. The system around it is not.

It is much easier to critique a homepage than to examine how incentives shape behavior across teams. It is simpler to change a CMS than to clarify who actually owns digital outcomes. It feels more concrete to debate design than to confront the fact that no shared model exists for how the business turns attention into revenue.

So the website becomes the proxy for deeper uncertainty. Fixing it feels actionable. Questioning the system feels abstract and uncomfortable.

But abstraction is precisely where the real constraints live.

The Shift That Changes Outcomes

Organizations that escape this cycle don’t start with a better design brief. They start with a different question.

Instead of asking how the website should look, they ask how it is supposed to function within the business. What decisions does it need to support? What behaviors should it encourage or discourage? What assumptions is it encoding about customers, sales cycles, and capacity?

Seen this way, the website becomes less of a deliverable and more of a diagnostic surface. It reveals where handoffs break, where feedback loops are weak, and where local optimization undermines global outcomes.

At that point, improvement stops being cosmetic. It becomes structural.

When the System Changes, the Website Follows

When marketing, sales, operations, and analytics are aligned around a shared understanding of the system they are part of, the website’s performance often improves without dramatic intervention. Messaging becomes clearer because it reflects real priorities. Data becomes useful because it informs actual decisions. Changes compound instead of resetting with each new initiative.

This doesn’t mean the website never needs to change. It means those changes are now informed by context rather than guesswork. They fit within the system’s capacity instead of overwhelming it.

The result is not a “perfect” website. It is a resilient one—capable of evolving without constant reinvention.

The Work That Actually Matters

Improving a website in any meaningful sense rarely starts with wireframes or technology choices. It starts with making the system visible: the constraints that shape behavior, the incentives that guide decisions, and the coordination limits that determine what is realistically possible.

This kind of work is quieter than a redesign. It doesn’t produce immediate visual artifacts. But it prevents the expensive, repeated failure cycles that so many organizations accept as normal.

Websites don’t fail because they are poorly built.

They fail because they are asked to succeed inside systems that cannot support the outcome.

Change the system, and the website usually takes care of itself.